What makes some countries rich and others poor? Is there any action a country can take to improve living standards for its citizens? Economists have wondered about this for centuries. If the answer to the second question is yes, then the impact on people’s lives could be staggering.

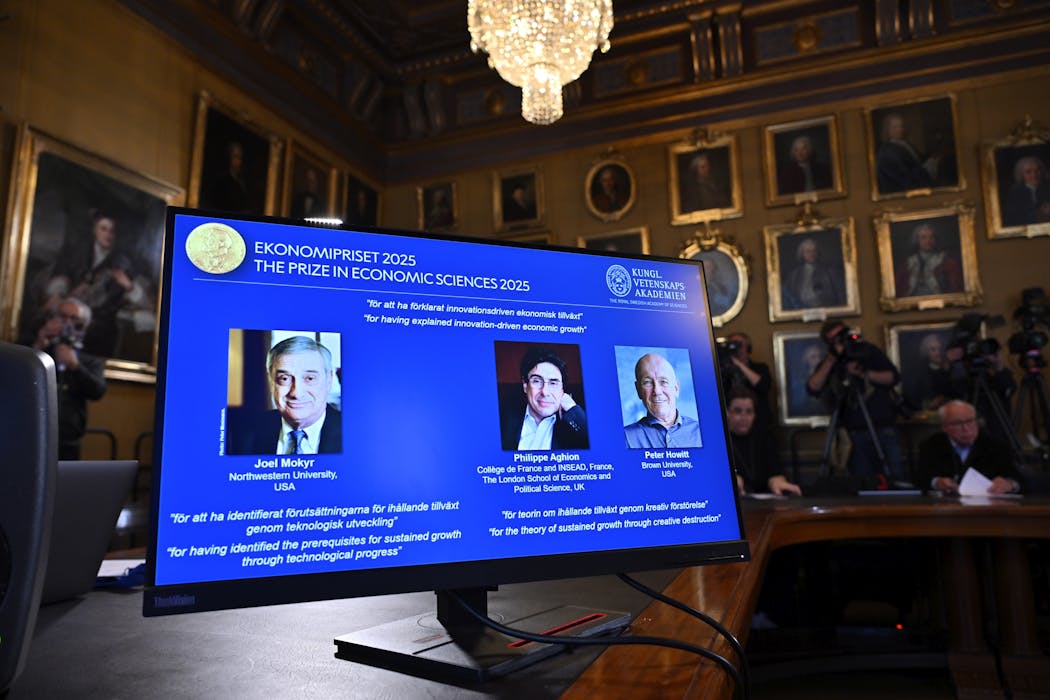

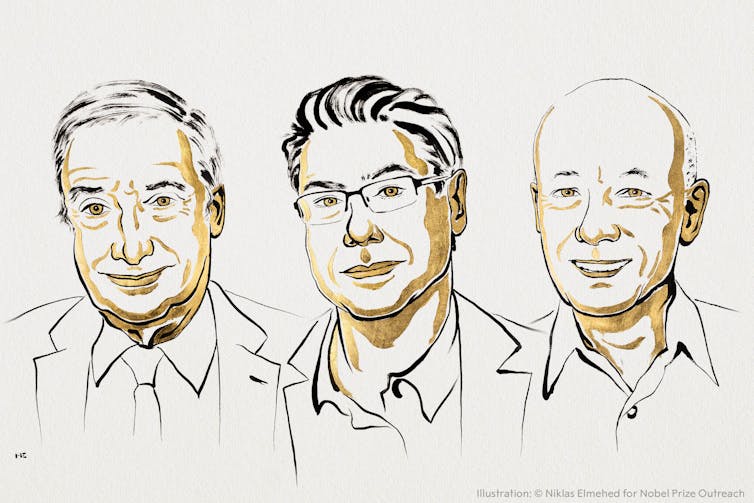

This year’s Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences (commonly known as the Nobel prize for economics) has gone to three researchers who have provided answers to these questions: Philippe Aghion, Peter Howitt and Joel Mokyr.

For most of human history, economic stagnation has been the norm – modern economic growth is very recent from a historical point of view. This year’s winners have been honoured for their contributions towards explaining how to achieve sustained economic growth.

At the beginning of the 1980s, theories around economic growth were largely dominated by the works of American economist Robert Solow. An important conclusion emerged: in the long-run, per-capita income growth is determined by technological progress.

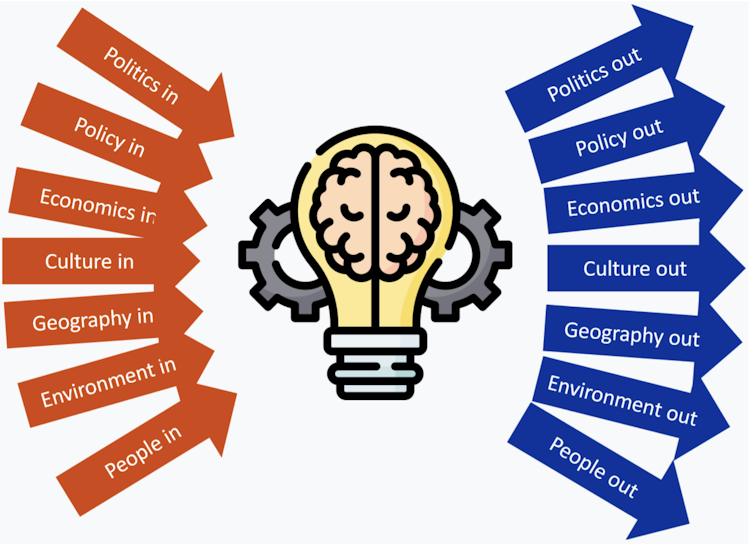

Solow’s framework, however, did not explain how technology accumulates over time, nor the role of institutions and policies in boosting it. As such, the theory can neither explain why countries grow differently for sustained periods nor what kind of policies could help a country improve its long-run growth performance.

It’s possible to argue that technological innovation comes from the work of scientists, who are motivated less by money than the rest of society might be. As such, there would be little that countries could do to intervene – technological innovations would be the result of the scientists’ own interests and motivations.

But that thinking changed with the emergence of endogenous growth theory, which aims to explain which forces drive innovation. This includes the works of Paul Romer, Nobel prizewinner in 2018, as well as this year’s winners Aghion and Howitt.

These three authors advocate for theories in which technological progress ultimately derives from firms trying to create new products (Romer) or improve the quality of existing products (Aghion and Howitt). For firms to try to break new ground, they need to have the right incentives.

Creative destruction

While Romer recognises the importance of intellectual property rights to reward firms financially for creating new products, the framework of Aghion and Howitt outlines the importance of something known as “creative destruction”.

This is where innovation results from a battle between firms trying to get the best-quality products to meet consumer needs. In their framework, a new innovation means the displacement of an existing one.

In their basic model, protecting intellectual property is important in order to reward firms for innovating. But at the same time, innovations do not come from leaders but from new entrants to the industry. Incumbents do not have the same incentive to innovate because it will not improve their position in the sector. Consequently, too much protection generates barriers to entry and may slow growth.

But what is less explored in their work is the idea that each innovation brings winners (consumers and innovative firms) and losers (firms and workers under the old, displaced technology). These tensions could shape a country’s destiny in terms of growth – as other works have pointed out, the owners of the old technology may try to block innovation.

This is where Mokyr complements these works perfectly by providing a historical context. Mokyr’s work focuses on the origins of the Industrial Revolution and also the history of technological progress from ancient times until today.

Mokyr noted that while scientific discoveries were behind technological progress, a scientific discovery was not a guarantee of technological advances.

It was only when the modern world started to apply the knowledge discovered by scientists to problems that would improve people’s lives that humans saw sustained growth. In Mokyr’s book The Gifts of Athena, he argues that the Enlightenment was behind the change in scientists’ motivations.

Ill. Niklas Elmehed © Nobel Prize Outreach

In Mokyr’s works, for growth to be sustained it is vital that knowledge flows and accumulates. This was the spirit embedded in the Industrial Revolution and it’s what fostered the creation of the institution I am working in – the University of Sheffield, which enjoyed financial support from the steel industry in the 19th century.

Mokyr’s later works emphasise the key role of a culture of knowledge in order for growth to improve living standards. As such, openness to new ideas becomes crucial.

Similarly, Aghion and Howitt’s framework has become a standard tool in economics. It has been used to explore many important questions for human wellbeing: the relationship between competition and innovation, unemployment and growth, growth and income inequality, and globalisation, among many other topics.

Analysis using their framework still has an impact on our lives today. It is present in policy debates around big data, artificial intelligence and green innovation. And Mokyr’s analysis of how knowledge accumulates poses a central question around what countries can do to encourage an innovation ecosystem and improve the lives of their citizens.

But this year’s prize is also a warning about the consequences of damaging the engines of growth. Scientists collaborating with firms to advance living standards is the ultimate elixir for growth. Undermining science, globalisation and competition might not be the right recipe.

![]()

Antonio Navas does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.