Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com.

Who invented the light bulb? – Preben, age 5, New York City

When people name the most important inventions in history, light bulbs are usually on the list. They were much safer than earlier light sources, and they made more activities, for both work and play, possible after the Sun went down.

More than a century after its invention, illustrators still use a lit bulb to symbolize a great idea. Credit typically goes to inventor and entrepreneur Thomas Edison, who created the first commercial light and power system in the United States.

But as a historian and author of a book about how electric lighting changed the U.S., I know that the actual story is more complicated and interesting. It shows that complex inventions are not created by a single genius, no matter how talented he or she may be, but by many creative minds and hands working on the same problem.

Making light − and delivering it

In the 1870s, Edison raced against other inventors to find a way of producing light from electric current. Americans were keen to give up their gas and kerosene lamps for something that promised to be cleaner and safer. Candles offered little light and posed a fire hazard. Some customers in cities had brighter gas lamps, but they were expensive, hard to operate and polluted the air.

When Edison began working on the challenge, he learned from many other inventors’ ideas and failed experiments. They all were trying to figure out how to send a current through a thin carbon thread encased in glass, making it hot enough to glow without burning out.

In England, for example, chemist Joseph Swan patented an incandescent bulb and lit his own house in 1878. Then in 1881, at a great exhibition on electricity in Paris, Edison and several other inventors demonstrated their light bulbs.

Edison’s version proved to be the brightest and longest-lasting. In 1882 he connected it to a full working system that lit up dozens of homes and offices in downtown Manhattan.

But Edison’s bulb was just one piece of a much more complicated system that included an efficient dynamo – the powerful machine that generated electricity – plus a network of underground wires and new types of lamps. Edison also created the meter, a device that measured how much electricity each household used, so that he could tell how much to charge his customers.

Edison’s invention wasn’t just a science experiment – it was a commercial product that many people proved eager to buy.

Inventing an invention factory

As I show in my book, Edison did not solve these many technical challenges on his own.

At his farmhouse laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey, Edison hired a team of skilled technicians and trained scientists, and he filled his lab with every possible tool and material. He liked to boast that he had only a fourth grade education, but he knew enough to recruit men who had the skills he lacked. Edison also convinced banker J.P. Morgan and other investors to provide financial backing to pay for his experiments and bring them to market.

Historians often say that Edison’s greatest invention was this collaborative workshop, which he called an “invention factory.” It was capable of launching amazing new machines on a regular basis. Edison set the agenda for its work – a role that earned him the nickname “the wizard of Menlo Park.”

Here was the beginning of what we now call “research and development” – the network of universities and laboratories that produce technological breakthroughs today, ranging from lifesaving vaccines to the internet, as well as many improvements in the electric lights we use now.

Sparking an electric revolution

Many people found creative ways to use Edison’s light bulb. Factory owners and office managers installed electric light to extend the workday past sunset. Others used it for fun purposes, such as movie marquees, amusement parks, store windows, Christmas trees and evening baseball games.

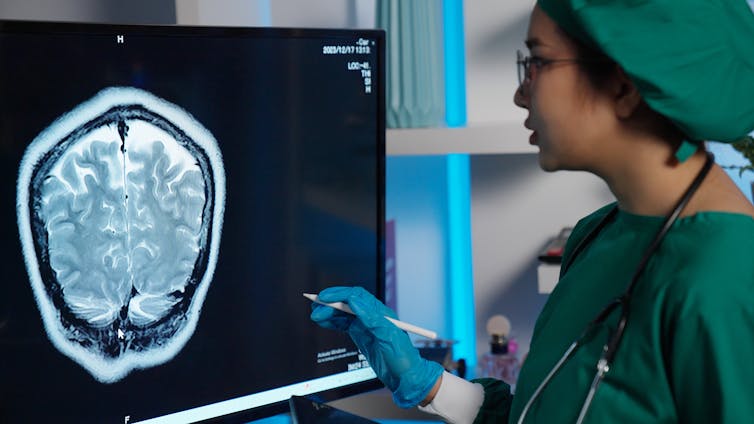

Theater directors and photographers adapted the light to their arts. Doctors used small bulbs to peer inside the body during surgery. Architects and city planners, sign-makers and deep-sea explorers adapted the new light for all kinds of specialized uses. Through their actions, humanity’s relationship to day and night was reinvented – often in ways that Edison never could have anticipated.

Today people take for granted that they can have all the light they need at the flick of a switch. But that luxury requires a network of power stations, transmission lines and utility poles, managed by teams of trained engineers and electricians. To deliver it, electric power companies grew into an industry monitored by insurance companies and public utility regulators.

Edison’s first fragile light bulbs were just one early step in the electric revolution that has helped create today’s richly illuminated world.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

![]()

Ernest Freeberg does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.